Money is a subject we shy away from talking about, whether it is with clients or our own financial situation. This is compounded by the attitude, in the UK at least, that it is not the done thing to talk about money, it has a taboo surrounding it. In the current supply and demand staffing issues we might expect salaries to increase but practices continue to say this is impossible. Vet salaries have been stagnant for over a decade while inflation continues to cheapened our money and student debt has massively increased. Could we be missing out on a key reason for the current staffing issues in the profession by not considering if salaries are part of the problem? Are they fair? What does a competitive salary mean? Why is it that it is easier to get a pay rise by moving jobs than by negotiating in the current practice? Let’s dive in.

Are salaries important?

Salaries are a strong factor in judging your self-worth and appreciation, no matter what psychologists say about money being a poor motivator. It probably is a poor motivator if the rest of the job is good but if your hours are long, you don’t get paid overtime, you miss out on life events at weekends and evenings, are stressed by the emotional burden from working in the profession and dealing with clients, salary DOES matter. Plus, with rising student debt and spiralling house prices, there is ever more debt to finance.

The RCVS 2019 Survey of the profession shows that the top three things that would make the profession a better place to work for vets are better work-life balance, better financial reward and less workload pressure. Pay is also consistently cited by survey respondents as a reason to leave the profession. Weirdly though, employers did not cite salary/pay/renumeration as a reason for people leaving their employment even though it would be an easy way of a departing employee to give feedback to a practice without it being personal.

A salary needs to be a fair compensation for the work done and money is needed to pay bills, mortgages, and service student debt, so yes, salaries are very important to us all. It is also part of our value and self-worth, whether it is good to tie it to it or not, and employers show their appreciation for our work though the money they pay us in exchange for the work we do for them; whether they should also show it in other ways is for another discussion.

What are current salaries?

A survey jointly carried out by BEVA and the BSAVA in 2019 indicated that most vets (41%) earn a salary of somewhere between £36,000 and £55,000 a year. The second most prevalent salary bracket (27%) was £25,000 to £35,000. The mean salary in the UK for full-time work in 2020 is £36,834. I’m going to be controversial here and state that in general vet salaries are not bad if compared to average salaries in the UK. Many of us vets can live comfortably and well above average UK salaries. However, does the salary seem fair when we consider the length of training, high level of skills required and the stresses and emotional burdens of the job?

The veterinary salaries don’t go as far as they used to especially regarding housing. It used to be the norm that housing was included as a benefit especially for new and recent graduates. It certainly wasn’t salubrious accommodation in the most part, but it allowed young vets to save money for buying a house or investing in buying in to a partnership. However, this is no longer the case and house prices have increased exponentially over the past couple of decades meaning that house ownership in some areas of the country is increasing unlikely even for highly qualified and skilled professionals like vets. I certainly could not afford to buy my house again that I bought 15 years ago and I hear frequent stories of vets and nurses unable to afford to live in the areas they work.

Are salaries fair?

Degree educated people can earn more in other professions and this is partly where fairness comes into it. For example, the average salary of a pharmacist (a degree educated professional employed in private company) is just under £45,000. Using the stick of the vocation of veterinary work to justify chronically underpaying staff is not fair. Even if vets would not want to work in these other professions, other jobs can give good salaries (say three-quarters of your vet salary) but in businesses that do not have the stressors and emotional burdens of vet profession and for many this is worth it and hence a good part of the reason for diversification away from clinical roles. We also need to consider that it is a global market for clever and intelligent people with a flexible skill set. Now vet practices are not just competing with other UK practices for staff but a global market for vets (shortages in North America, Australia and New Zealand) and more concerning, competing with other business that will pay much better for highly employable veterinary staff – some will pay better, often they have better benefits packages, most have a lower stress, and highly likely that truly flexible working patterns are available. European vets who were once drawn to the UK for the relatively good salaries they could achieve here are increasingly finding that the salaries in their own countries have increased while still having a cheaper cost of living than the UK; this is compounding the problems caused by BREXIT and the COVID pandemic.

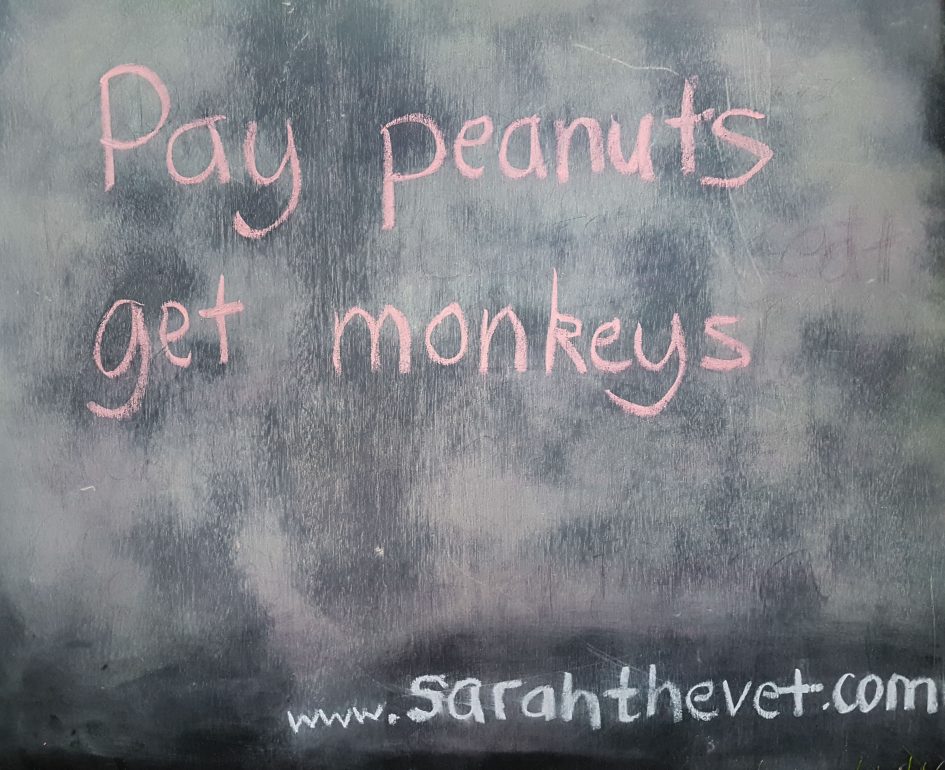

There is very little career progression within the profession and hence poor salary progression. In fact, it seems to be so normal not to receive any annual salary increase at all yet without an increase of at least the cost of general inflation employees are getting to enjoy a relative pay cut. Who would stand for a pay cut? And sadly, it is normal that significant pay increases can only be achieved by moving jobs not negotiating with the current employer. The corporate groups have pay scales, but these are often stifled by strict hierarchies which mean a valuable member of a team cannot be recruited as they couldn’t be paid the market rate, especially for top candidates. In the same corporation, members doing the same job on different sites may well have very different salary or benefits (yes, it is true).

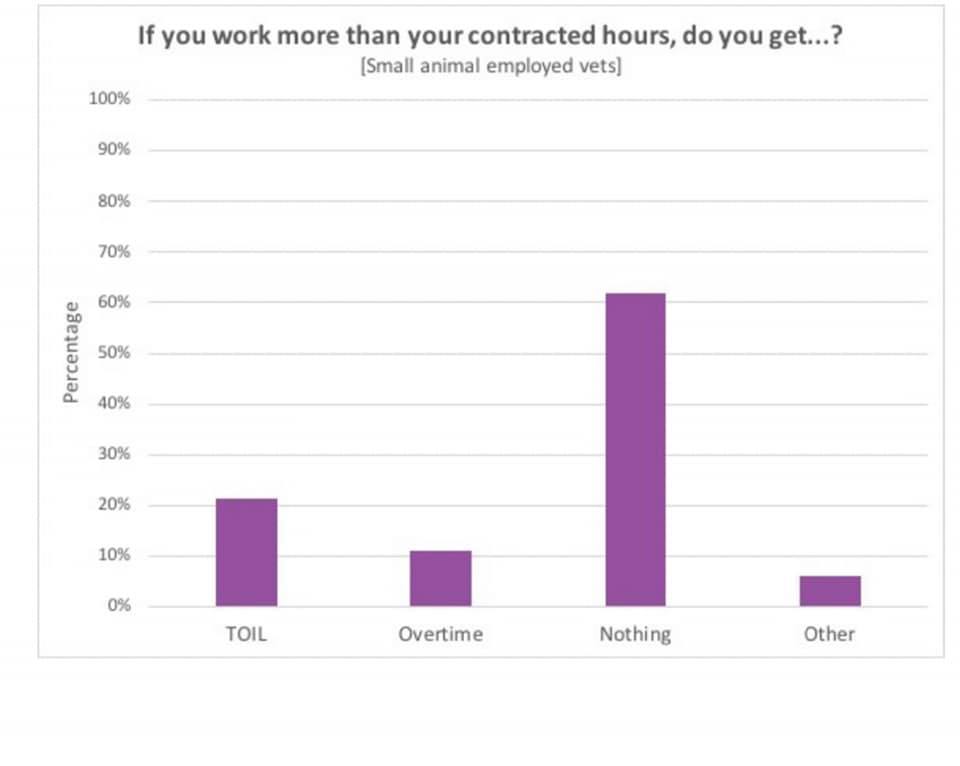

We need to mention unpaid overtime which is still the norm in the profession – the recent Onswitch survey showed that 60% of small animal vets work overtime that is not compensated by time off or monetarily. We all know this job struggles to have fixed hours but when overtime work is frequent and more than a fraction of the shift length, it should be compensated. Loving your job and not wanting to work hours of unpaid overtime are not mutually exclusive. This is something that needs to change in the profession – it is something that vets consistently look for when comparing jobs.

What about benefits?

Benefits are non-wage compensations that supplement a salary package. In the vet profession in the UK, the norm is to pay the statutory minimum in benefits, in other words the least the business can get away with legally. Even most big veterinary businesses in the UK are universally poor in the benefits rewards. This means that holiday is still 4 weeks plus bank holidays (some are increasing to 5 weeks, but often pro rata can leave people short when worked out hourly). This means sick pay is often zero from the practice with statutory sick pay of about £100 a week from the government. This means maternity leave is the lowest possible and the lowest in Europe. This means that pension contributions are the minimal legally required. What this means is that businesses are not taking care of their people when their staff most need it such as an accident or sickness, or holiday time to recover from the stress of work. And then if you a woman and have a child, you are screwed by the maternity leave that means too often return to work before you are ready (and with no provision for nursing a baby or expressing milk or working hours that fit around childcare) and not uncommonly a dilemma that the business will not let you return on reduced hours, especially if in management or senior position – full-time or the highway is all too common. This is not acceptable in modern world and in a profession of 75% women – is it a wonder that female vets struggle to come back to work after having children?

Some practices provide benefits such as RCVS membership, VDS cover, and an association membership though realistically these are an absolute for working or obtained as a package at great discount by head office. Other benefits such as perk box, gym membership are marginal benefits – they are low cost especially if obtained in bulk and written off against tax and do not provide a benefit for all. Especially when compare with benefits such as 20% salary contribution to a pension which are not uncommon for high value professions, except vets.

One benefit that is often of great value to veterinary staff is that of pet treatment discount and the option of taking your dog to work. Yet for a profession where we expect caring pet ownership, these benefits are surprisingly rare. And often vets and nurses work such hours that they cannot reasonably have a dog and yet the greatest teacher, especially for empathy, is often our own pets.

Let me get this straight, it is not a staff benefit to get a lunch break, it is legally mandated minimum. Advertising that staff get their lunch break is a joke.

Issues outside salary

Let’s face it – on call is an issue. It is not fairly compensated for providing a stressful service in uncomfortable and unsocial hours that have a large impact on life outside work. Several surveys in the profession have shown that salaries are higher in jobs that don’t have on call, even for the same type of work. We also have a problem that on call is not counted as work and yet it is not not work yet it is often more stressful and disrupting than any other veterinary work. And then we really haven’t worked out how to allow people who have worked in the night on call to have rest and recovery time so it is still normal that vets are asked to sign out of the working time directive. Is it little wonder that jobs that have a requirement for on call or weekend working are less popular?

Student debt is rising at unprecedented levels, such that UK vet students graduate with an average of £70,000 for home students. These debts take many years to pay off and reduce the effective income and borrowing potential of the new graduates. There is some sign the new graduate pay is increasing faster those more qualified, but this has led to the situation where vets a few years out are being paid less than the new grads and may even be expected to mentor and teach them. It will also mean that a good percentage of new grads will have to choose their first job primarily on salary in order to service these debts.

And what about nurses?

And now I come on to nurses, who I’m sure all will agree are universally underappreciated and underpaid. They can earn as much stacking shelves in supermarkets as the rate in many practices (for example a corporate group (V4P) nurse average wage is £11 an hour) and without the stress and complex hours of working in veterinary practice. A registered human nurse in a nursing home can get £21.49 an hour, with paid breaks, for a non-senior role in a care home. The fact is that many nurses struggle to afford to live on their salary and rely on house share/partners or taking all the extra work they can to afford to live. I know many nurses who are not earning the living wage. And then if they were to have children, they are often paying to work once childcare is paid for. No wonder it is rare to find a nurse working in clinical situations who is older than their mid-thirties. The RCVS survey of the nursing profession consistently finds that they are dissatisfied overall with their salary/ remuneration level. Inadequate reward is seen as a major contributing factor to the lack of respect for the vet nurse role and to vet nurses leaving the profession.

So what are we worth?

Lastly, we come on knowing what our worth is (and this is now in the context of not only in the UK but world-wide and not just the veterinary profession but the whole work environment) and being empowered to ask for it. ‘Competitive salary’ is meaningless when there is so little to compare the salary to within the profession but very clear figures to compare it to outside the profession. There are very few salary surveys, each of which is biased in its own ways. Women are less likely to negotiate a higher salary and underestimate their worth leading to a shocking gender pay gap. I strongly feel that veterinary business management and economics should be a core subject at vet school – I qualified 19 years ago and I wasn’t aware of these subjects until 10 years ago. This will help us understand our worth in the context of business. Change may be happening as younger (than me) generations seem to be more aware of their worth and are not scared to ask for it.

Employees ask for fairness in pay which means published salary scales, not hiding them as a trade secret, and understanding how we fit in the business. When there is universal knowledge of what we should be earning then large companies have less power to pressurise salaries to be lower and lower and the individual has more power to ask for what is right. For some this will be a painful experience that their expectations of salary are not going to be met by reality, but then they know they can do something about it – upskill, diversify or find a better paid job.

Summary

Veterinary employers may need to increase salaries in the short term to overcome the retainment crisis that is driving people away from the profession and in the long-term offer more sustainable salaries and benefits that are meaningful to reduce the pull to jobs where they are much more generous. And I mean benefits in the broadest sense – not yoga at lunch or pizza on busy days, but meaningful benefits to working like being able to pick up children from school, to be able to go to your sister’s wedding in 6 months time, to not get to the end of the week and feel drained of all energy with an empty bank account. Like with recent changes in maternity leave benefit in some companies, things can move in the right direction. With more transparency and discussion, then we can hope to reduce the gender pay gap and make salaries fair for all those who work in the profession. Wage increases are needed such that people feel it is ‘fair’ for the job they do, but these need to be funded from somewhere. We need solutions not companies saying it is not possible – what do you think?

16 October 2021 at 5:08 am

I absolutely agree with all that you are saying. It’s especially galling that in this day and age there is still a gender pay gap. Men are so much better at demanding- and this is rewarded.